Like much of Paul Thomas Anderson’s work, the BOOGIE NIGHTS screenplay has an odd structure, divergent POV and a hefty length, yet every page of it is full of worthwhile lessons for screenwriters.

Here are ten:

Conflict doesn’t need to be constant

western“>Conflict is often billed as screenwriting currency: you’re not going anywhere tense or eating anywhere dramatic without it. And yet the first half of the BOOGIE NIGHTS screenplay (aside from a poster-ripping fight between Dirk and his mother) is a pretty easy ride for the protagonist.

western“>It’s the nature of any medium that, after a certain amount of time, there are trends that become so prevalent they form a kind of language:

- The image of a dog in art representing fidelity.

- Items of a different sheen in a video game being those you can interact with.

- More relevantly, the understanding that protagonists in film will, at some point, suffer.

western“>Through this language, you can make comfortable assumptions about what your audience will comfortably assume, and this is precisely why the seemingly smooth and conflict-less ‘rise’ of Dirk Diggler works. We know that films are structured around conflict; we come to expect some level of failure or suffering on the part of the protagonist. So, when that suffering is withheld, the effect is quite jarring.

The audience is left waiting for something to go wrong, and the longer it doesn’t, the more palpable the expectation becomes and the more the tension seeps into seemingly happy scenes. In a way, it plays on that same tension that drives theatrical tragedy: you know categorically that the protagonist is going get shivved by their own pride, but not how or when.

western“>Films are often praised for subverting expectations, but it can be just as effective to meet them late.

Tone is a balancing act

western“>Tone, much like marriage and the consistency of yoghurt, is generally less effective when it’s uneven. It’s crucial to the expectations discussed above that the tone of the film lays down those expectations in the first place. We wouldn’t expect a dramatic ‘downfall’ if the film were too funny, for example, which would ruin the tension.

western“>The BOOGIE NIGHTS screenplay is all the more interesting for actually managing to carry an uneven tone to great effect. No scene captures this better than the one in which Little Bill kills his wife, her lover, and himself.

western“>It’s like the film in microcosm: a big daft party suddenly descending into hardship and violence. This scene is the unexpectedly dark punchline to a recurring joke (that Bill’s wife remorselessly cheats on him while he gets increasingly angry), and is the cinematic equivalent of a peaceful family board game during which your second cousin is suddenly taken to task about their alcoholism.

western“>There are two reasons it works. The first is the effect of the tonal shift: it marks the midpoint of the narrative and the beginning of the descent, yet is immediately followed by another shift in tone with Amber’s unintentionally comedic documentary footage from a decade later. We don’t get to see the aftermath of Bill’s action – it’s seemingly back to business as usual – though Amber’s footage fittingly includes discussions of violence in film.

western“>Bill’s action is the jarring warning shot, the sign that the humour and success can’t last and, of course, the rest of the film is peppered with violent events just like it, despite the fake-out of Amber’s funny film.

western“>The second reason is the portmanteau-like structure of the BOOGIE NIGHTS screenplay. Once Dirk has become a part of the porn social circle, the narrative flits between characters, some with sad stories (Amber), some with funny ones (Scotty J). For this reason, an overall tone is never set in stone, allowing for the story to take sudden dark or comedic turns without breaking its own rules.

Using setting to enhance a scene

western“>It seems like an obvious point – and it is – but it’s something that’s often done in the simplest and most obvious way. A passionate kiss in heavy rain or a rushed discussion about important issues while walking down a long and business-like corridor are both instances in which setting complements situation, but they’re a fair few rungs below innovative.

western“>Anderson takes a different approach in the BOOGIE NIGHTS screenplay. If we take the scene with Alfred Molina’s unhinged Rahad Jackson; it’s a set up often seen in film:

- an arranged ‘deal’ in which the hero(es) aim to outwit their fellow dealer.

- They either don’t bring the stuff or show up with a friend having been told to bring no-one or take a punt on changing the terms.

- The dealer is some volatile maniac who could snap any second.

Will they or won’t they get away with it? That’s the basis of the tension.

western“>Typically this kind of scene is played quiet (the scene from BREAKING BAD in which Jesse and Walter meet Tuco in the desert, or the one in DJANGO UNCHAINED in which Shulz and Django barter with Candy are good examples), tension building as the heroes risk mortally provoking the antagonist.

western“>Anderson goes the complete opposite way, with Jackson’s friend Cosmo repeatedly setting off firecrackers in an ample living room, all to the tune of Jesse’s Girl played at an embolism-inducing volume. The constant tiny explosions massively enhance the dynamic of the scene: Dirk, Reed and Todd jump at each one while Jackson barely notices, showing their fear and his slightly unhinged mind.

Subplot Sparsity

western“>The perfect example in the BOOGIE NIGHTS screenplay is the subplot involving Amber’s custody battle for her son. It’s a dramatic enough series of beats to warrant more screen time, but Anderson covers it in:

- a phone call

- a drug-fuelled conversation

- a court meeting

western“>Obviously, the purpose of any subplot is to buttress the non-subplot, but the risk is that it will in some way distract from the core thrust of the narrative. Amber’s subplot works so well because it is entirely complementary, i.e. there is no part of her secondary narrative that is irrelevant to the primary one.

western“>A common theme that emerges throughout the film is one of family; lost people finding solace in each other’s company. Amber’s subplot is the epitome of that theme, and, more pertinently, it is the principal explanation for the nature of her relationship with Dirk in the main plot. She has, essentially, lost a son, a role that Dirk comes to fill as the story moves forward.

Telling one story with several

western“>Writing a focused screenplay is naturally more difficult when the story involves multiple narrative strands. In ensemble stories like the BOOGIE NIGHTS screenplay, there’s always a risk that the end result won’t form a cohesive enough whole, but Anderson is careful to ensure that each works towards the same goal.

western“>Firstly, the splitting of the narrative only really comes into play after we have met all the characters over a series of parties: we get to know them as a group first and foremost, which helps reinforce their respective hardships once the tone shifts (see above) and we suddenly see them alone.

western“>The main strands follow Amber, Buck, Jack and Dirk and, crucially, all four follow similar beats:

- Amber fails to get custody of her son due to her profession.

- Buck is denied a lone and ends up opportunistically stealing money.

- Jack tries to shoot a more off-the-cuff scene, an act that unpredictably culminates in him beating up a stranger.

- Dirk makes a failed attempt at a music career then gets beaten up for agreeing to masturbate in front of a stranger for money.

western“>The reason this fracturing works is because every strand is answering the same question: how does working in pornography affect this person? We don’t follow one character as they boat on a serene lake and another as they assassinate diplomats; we follow people dealing with similar struggles, namely the effects of an ever-changing industry on characters who can barely keep up.

western“>Essentially, every narrative strand meets the same brief.

Timing is everything

western“>This follows on from the above. When narrative and POV are split, structure becomes ever more important: dramatic beats have to synchronise to some extent, else the various set-ups and pay-offs will disintegrate

western“>The best example is the inter-cutting of Jack and Rollergirl’s failed porn shoot and Dirk’s beating after taking money to masturbate for a stranger.

western“>They are essentially the same scene, but reversed – both involve:

- a sex act (Rollergirl and the stranger; Dirk masturbating for money).

- a trick regarding the identity of the partner(Rollergirl’s schoolmate; a man looking to beat up a homosexual rather than a man after gratification)

- someone getting kicked a lot (the schoolmate; Dirk).

The key difference is the person on the receiving end of the violence (in one they’re the victim, in the other the perpetrator).

western“>It’s a nice way of showing that the struggles these characters face come both from within and without: they’re just as much to blame for what’s happening to them as the changing industry and the stigma surrounding it. Putting the two scenes at the same point in the story, and timing each of their beats to coincide, is what allows this comparison to stand up so well.

Dialogue doesn’t always need to move the story forward

western“>It’s often said that dialogue, on top of being, you know, good, should help propel the narrative, but, as the BOOGIE NIGHTS screenplay demonstrates, it’s too narrow a rule.

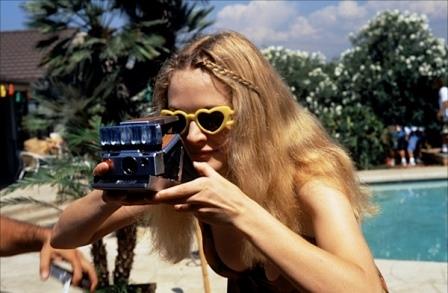

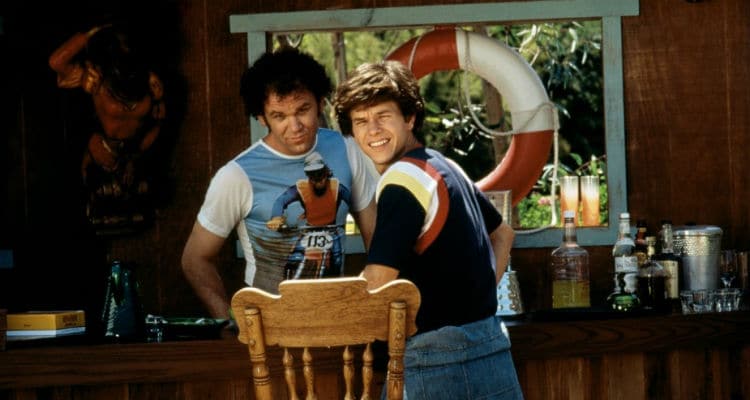

western“>

western“>To massively oversimplify the film, BOOGIE NIGHTS introduces the world of pornography during its first half, and then breaks it during the second. But that world – the sex, excess, craziness, partying, odd characters – needs setting up enough that dismantling it actually means something, and seemingly extraneous dialogue is often the prefect way to do so.

western“>Take the exchanges between Dirk and Reed at their first meeting. They talk about working out and they talk about diving.

western“>It doesn’t further the story because there isn’t strictly speaking any ‘story’ happening at this moment. It’s world building. On one level it’s character development for Dirk and Reed and their underlying competitiveness and on another it’s a more general demonstration of the type of lost characters who are drawn to this environment in the first place.

western“>For the scene to be purely functional, Dirk would simply need to attend the party, meet the money men, and ensure his job as a porn actor. That’s all we need as far as getting to the next scene. Anderson’s decision to take a little longer is what allows the second, more eventful half of the film to hit as hard as it does.

Using time skips

The BOOGIE NIGHTS screenplay skips over significantly chunky periods of time, and often the temptation when doing so is to ‘wrap up’ each section neatly before moving onto the next. That’s all well and good, but these sudden leaps can be used in a more interesting way.

The leaps forward specifically cut short significant events. Little Bill kills himself… Suddenly we’re in the next decade. Buck steals money from the aftermath of a robbery gone awry… We jump forward to Todd’s disastrous plan to rob Jackson.

Using these jumps to deprive the audience of the immediate aftermath of some of the film’s most crucial moments is an effective narrative technique because it ‘colours’ the next time frame without losing any dramatic momentum. When Bill’s blood splatter jumps to the ’80s’ title card or when Buck’s blood-soaked money fades into ‘Long Way Down’, the tone for what follows is abruptly set.

Break the mold with your protagonists

western“>This is a small point but a noteworthy one: protagonists in film (outside of comedy) are rarely stupid. Their actions may be, but their manner rarely matches. There is a kind of uniformity to protagonists in film. They’re quick-witted, intelligent but troubled, world-weary, socially over or under-confident and so on. But not stupid. Not often.

western“>

western“>Dirk in the BOOGIE NIGHTS screenplay on the other hand:

western“>’It is. It’s jealousy. It’s deceitfulness. It’s vindictiveness. It’s all of that stuff, you know? But, I mean, God, what can you expect when you’re on top, you know? It’s like… Napoleon. When he was the king, you know, people were constantly trying to conquer him, you know, in the Roman Empire.’

western“>It’s rare to hear the above speech pattern come from a protagonist outside of a comedy, and that’s part of what makes him endearing. It sells us on his naivety and innocence, accounts for his mistakes and pride and, best of all, it’s weird.

western“>He’s just an unusual protagonist, and there’s a lot to be said for something as simple as imbuing a lead character with undesirable traits that are actually, for want of a better word, less (cinematically speaking) ‘cool’.

Once your ‘outsider’ character is ‘in’, you’re free to switch focus

western“>We’ve talked before about the function of ‘outsider’ characters; those who find themselves in strange environments and act as a vessel through which the audience can come to understand it. They are often protagonists in their respective narratives, and you could easily put Dirk Diggler into that ‘outsider’ category.

western“>The interesting decision Anderson makes in his BOOGIE NIGHTS screenplay is to gradually dilute Diggler’s role once he’s ushered us in. He never falls off the ‘protagonist‘ pedestal, but his point of view becomes less and less central, as discussed above.

western“>It makes sense: the initial function of an ‘outsider’ character is to justify explanation of setting, custom, character – essentially the world of the film. Once that’s accomplished, why limit yourself to such a narrow view of the world you’ve just built?

western“>Of course, it’s very much dependent on the type of film, but sticking religiously by a character’s side once the narrative need to do so has expired is a limitation no-one needs to heed.

If you enjoyed this article, why not check out our article containing 10 Screenwriting Lessons From DEAD MAN’S SHOES (2004)?

– What did you think of this article? Share it, Like it, give it a rating, and let us know your though in the comments box further down…

– Struggling with a script or book? Story analysis is what we do, all day, every day… Check out or range of services for writers & filmmakers here.

Get *ALL* our FREE Resources

Tackle the trickiest areas of screenwriting with our exclusive eBooks. Get all our FREE resources when you join 60,000 filmmakers on our mailing list!